It’s time to change our methods of food production.

I was always dazzled by the markets in Southeast Asia. Whether I was in Vietnam or Laos, the open-air markets were always teeming with stalls of leafy vegetables, tropical fruits, mountains of rice, pungent fish and meat, and fluffy pastries. Even with the difference in currency and income, it seemed that locals of all economic backgrounds could purchase enough whole foods to create a meal that nourished the body and fed the soul.

Returning to American supermarkets is always both overwhelming and disappointing. Aisles upon aisles of processed food dominate the space, and as my visiting Moroccan friend once exclaimed in horror, our produce is nearly scentless. One late night in a New Orleans neighborhood, I wanted nothing more than a fruit or some veggies, but after driving to two gas stations and a CVS, I had nothing: no solitary banana, no sealed fruit in a cup, not even a bag of carrot sticks. Exiting the gas station, I saw a neon row of fast-food restaurant signs beaming at me across the street.

A plate of food is a snapshot of culture and history; it reveals a consumer’s socioeconomic status, geographic location, even religious views. But how is one family able to enjoy a meal of local, organic produce while another family doesn’t have the time or money to do much besides heat up heavily processed frozen foods? The system of American food production is steeped in inequality.

I believe a fair starting point lies within the Green New Deal, a 14-page proposed resolution that is ambitious, sustainable, and completely possible with the cooperation of all. It would not only begin healing marginalized communities from pollution-induced disease and economic injustice, and it would also diminish American company-produced emissions that affect global communities who are already seeing the drastic effects of climate change.

The Green New Deal goes beyond the shortcomings of green capitalism and individual lifestyle changes attainable only by the upper-middle class. Instead, it proposes shifting away from fossil fuels onto renewable energy, creating thousands of jobs with dignified working conditions and living wages. The Green New Deal proposes “… working collaboratively with farmers and ranchers in the United States to remove pollution and greenhouse gas emissions from the agricultural sector as much as is technologically feasible… by supporting family farming; by investing in sustainable farming and land use practices that increase soil health; and by building a more sustainable food system that ensures universal access to healthy food.”

So how do we begin to enact the steps to achieve this vision? First, by critically examining the current American system of agriculture, we see how these patterns replicate themselves in a global context, and we begin to see where there is space for radical justice and improvement.

Factory farming

The food sector accounts for nearly one-third of global emissions of greenhouse gases, and meat and dairy comprise almost half of this amount and spew methane. Nearly everyone has heard of or seen a documentary that highlights the flaws in our system of factory farming then leads to a call to go vegetarian or vegan as the best way to solve environmental crises. However, indigenous communities have historically consumed animals respectfully and sustainably, while others continue to do so today.

Factory farming is a symptom of our capitalist system that must be eradicated. Under capitalism, farm animals are seen as sources of profit. Because capitalism requires a profit motive, the exploitation of animals, humans, and the Earth are necessary and deemed justifiable in order to turn a profit; when American workers can no longer be justifiably exploited, American companies begin to exploit laborers in the Global South for agriculture and other resources under imperialism, the highest form of capitalism. Capitalism argues that we must compete for scarce resources, which is a highly unsustainable system for a growing global population and finite resources. Eliminating meat or dairy from our diet won’t end the carbon emissions that come from plant agriculture, and besides, the exploitation of human workers is even more repulsive to me than the exploitation of animals.

Overexploited & Underpaid Workers

American agriculture is historically entrenched in the exploitation of workers in order to create a larger profit and concentrate power among a handful of wealthy people. From slaves to sharecroppers to migrant workers, farm workers have been used viciously, either enslaved or grossly underpaid. Their marginalized identity often places them on the vulnerable end of a power dynamic, coerced into accepting their poor working conditions out of desperation to survive. Those who harvest our food live in near poverty, unable to afford the hefty medical payments to treat cancer, infertility, and other health issues linked to exposure to agrochemicals.

Edgar Franks from Community to Community, an organization that works with farmworkers in Skagit County, Washington says, “When you compound working outside with harsh weather conditions, it’s a recipe for a disaster, a humanitarian crisis. A lot of that goes unnoticed as with other issues of immigrants and farmworkers. [Farmworkers] are affected by pesticides, the drought, poverty…when we think about climate justice, part of it is the environment and the resources, but it’s also about the consequences of being poor and being an immigrant that put you at a disadvantage because people don’t see you as a political force.”

The average age of an American farmer is 58 years old, and the average age of a beginning farmer is 47. Farming has traditionally been a family business, but future generations of would-be farmers are gravitating towards urban areas for higher education that can push them upwards socioeconomically. It’s entirely understandable considering that only 41% of small farmers are able to turn an annual profit. Without fair wages for farm workers and owners, the future of food production is compromised.

Unsustainable Centralized Production

Monoculture plantation growth methods of slavery-era cotton led to soil erosion on stolen land from Virginia to Alabama, stripping the land of its ability to produce crops in the future. Aaron Joslin, a PhD candidate at the University of Georgia who teaches about soils and hydrology, wrote that plantation owners “were completely unconcerned with their place in the ecology of their home, elevating the importance of themselves while devaluing the soil and its ecological functions that they depended on. The androcentric nature of their worldview allowed their greed and self-importance to prevail while undermining their empathy and pursuit of balance and harmony with the world around them.”

Plantation farming synthesized racial domination, profit, and exploitation of people and the earth. Nowadays, centralized food production utilizes endless acres for a monoculture that requires fertilizers, pesticides, herbicides and massive amounts of water. Mono-cropping further proves to be unsustainable as its lack of biodiversity leeches the soil of nutrients and requires ever-higher amounts of chemicals to grow, which become toxic runoff that infect our waterways.

Furthermore, the rise in extreme weather leads to poor harvest, food shortages, and price fluctuations when crops are destroyed by floods, storms, or droughts. When food production is centralized, meaning it is produced in one place and then transported elsewhere for consumption, these disasters become more likely to crush a larger crop that threatens millions of people with food insecurity.

Subsidized Crops that Create Health Issues

Since the Great Depression, the federal government has provided subsidies to agricultural producers to ensure they can still turn a profit in case of variations of weather, market prices, and environmental disaster. However, the vast majority of these subsidies go towards corn, soybeans, wheat, cotton, and rice, which incentivizes farmers to grow these crops over others.

The Environmental Working Group states that, “Despite the rhetoric of “preserving the family farm,” the vast majority of farmers do not benefit from federal farm subsidy programs and most of the subsidies go to the largest and most financially secure farm operations. Small commodity farmers qualify for a mere pittance, while producers of meat, fruits, and vegetables are almost completely left out of the subsidy game.”

The monocultural growth of these five crops play a huge role in creating highly processed foods that we readily consume, like cereal, French fries, and high fructose corn syrup found in nearly every packaged food, which lead to cardiovascular disease, obesity, type 2 diabetes, and other health issues. These foods are less expensive and easily accessible in convenience stores and fast-food joints, often limiting low-income Black and Brown families in their choice of food and pushing them down a path of health issues that eventually bankrupt families due to expensive healthcare bills.

Food Deserts

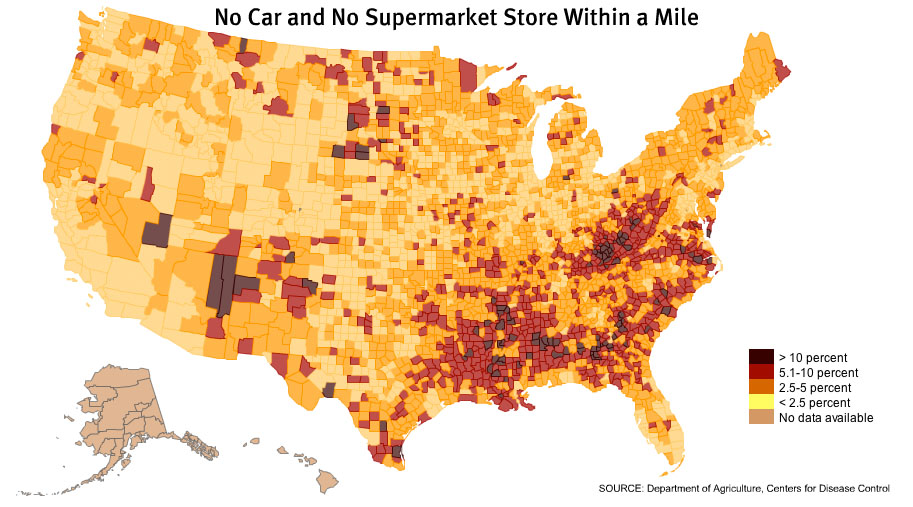

According to the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), a food desert is an area in which low-income communities lack access to fresh produce in large grocery stores. In urban areas, at least one-third of the population must live over a 1 mile away from the nearest large grocery store. In rural areas, at least one-third of the population must live more than 10 miles from the nearest large grocery store. Much of these populations do not own cars, further distancing them from food that nourishes the mind and body.

The “cold supply chain” has made storing and transporting food across time zones and hemispheres a reality, still remaining edible by the time it gets to the consumer’s plate. While we do see ripening produce in grocery stores, it is far cheaper to transport processed food with a longer shelf life. When our food is so processed, we are left with a severed connection of our understanding of food.

Furthermore, long distance transportation creates pollution, and the food passing through middlemen leaves produce too expensive for stores in low-income areas with high Black and Brown populations, a problem that contributes to the creation of food deserts.

So What Now?

Our food production systems have failed us, especially low-income Black and Brown populations. I like to imagine a world where fresh produce is easily accessible to all, and our plates are colored with food that was ethically and locally sustained. Whatever new systems we dream of must be thoughtfully compassionate, prioritizing people over profit. They must be decentralized, cooperative, and compensate workers fairly for their labor.

Next post, I’ll delve into more detail.

Recent Comments